Blacks Islamic History

Sunday, 1 April 2018

Blacks Islamic History: Blacks Islamic History: MUSLIMS AND JAZZ IN 1953

Blacks Islamic History: Blacks Islamic History: MUSLIMS AND JAZZ IN 1953: Blacks Islamic History: MUSLIMS AND JAZZ IN 1953 : ...

MUSLIMS AND JAZZ IN 1953

Muslims and jazz in 1953

by Ahmad Usman

|

From Ebony Magazine, April 1953

Today’s post is from an Ebony Magazine article published in 1953 that explored the growing popularity of Islam among Black American jazz artists. The article provides a window into the important connection between jazz and the spread of Islam among Black Americans from the 1940s onward — especially for those who identified with Sunni Muslim communities or the Ahmadiyya movement. It centers around the saxophonist Lynn Hope (also known as El Hajj Abdullah Rasheed Ahmad), who served as a leader and teacher of a Sunni Muslim community in Philadelphia that was affiliated with the historic Adenu Allahe Universal Arabic Association founded by Professor Muhammad Ezaldeen. A few other iconic be bop jazz artists are also mentioned including Art Blakey and Ahmad Jamal, both members of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community. The piece highlights Islam’s appeal as a potential antidote for the evils of white supremacy, anti-Black racism and racial oppression. The author recounts how Black Muslim jazz musicians like Hope and his band used their religious identity to subvert the discriminatory policies of segregation in the South. They were able to “pass” since Arabs and “Eastern peoples” were often designated as white in segregationist America. This was attractive to some, as it indicated one’s ability to reconnect to an affirming history and cultural identity, countering “any sense of inferiority as a Negro” as the article puts it. By allowing Black artists to pass, Islam also offered a potentially powerful survival tool.

Hope’s Islamic identity and practice permeated his daily life, including his performances. His “spectacular [musical] routine” in which he was known to “parade across the bar” is cited several times in the article, along with pictures of Hope standing on top of the bar sporting a white turban during a performance . Hope is, however, also depicted as being quite devout. Reading the article today, we might wonder whether or not he felt himself in a compromising position. By all accounts, Hope was an exceptionally knowledgeable Muslim who took his religion quite seriously. Yet his profession carried him into some spaces (i.e. on top of the bar) that many Muslims today would deem cringeworthy. But the article also discusses how Hope drew upon Islamic teachings to help guide his business practices, contracts, paying his band members and how he spent his income. Therefore, from another angle, we might take inspiration from his ability to skillfully navigate the music industry without hiding or compromising his faith. This last point is particularly salient for Muslims living in America today. Sixty-five years after this article was published Muslims still struggle with some of the same issues. For instance, how does one balance their professional life with a desire to pursue Islamic education? Today, we have weekend intensives and summer retreats. Hope took a year off from music to study Islam, along with history and Arabic, which enabled him to serve his religious community as a teacher. And while some Muslims work hard to avoid public displays of their faith on the job, Hope showed up to work wearing a turban.

We hope you enjoy this week’s fascinating retrospective!

Thursday, 14 September 2017

By AHMAD ZAKX UTHMAN

On 14/09/2017

time:11:47pm

On April 14th, 1972, a man claiming to be a Detective Thomas from New York City’s 28th

police precinct placed a call requesting assistance for a fellow

officer in distress. The call, later determined to be a fake, prompted

two officers to rush to the address, which was the Nation of Islam’s

Harlem Mosque # 7. The two officers “smashed their way into the 116th St. Mosque.”[1] This violated of the NYPD’s policy with regard to the Muslim place of worship.[2]

Members of the mosque felt compelled to protect the sanctity of the

space and the safety of the congregation. A fight broke out. It is

unclear exactly what happened, but in the ensuing melee, Phillip

Cardillo, one of the two officers who had burst into the mosque

unannounced, was killed.

More

officers rushed to the mosque, creating a scene that the Amsterdam News

described as an “attack” and “invasion”. Harlem residents, who saw the

mosque as an essential asset to the community, formed a crowd of

concerned onlookers. Minister Louis Farrakhan, the spiritual leader for

Mosque # 7 at the time, arrived along with Harlem Congressman Charlie

Rangel. Members of the Mosque of Islamic Brotherhood, Harlem’s principal

Sunni Muslim institution, rushed over to help ensure the safety of the

roughly three to five hundred members of Mosque # 7 who were trapped

inside the building. Minister Farrakhan urged the crowd, which had now

grown angry, to keep calm. He and Congressman Rangel worked out a deal

with NYPD’s Chief of Detectives Albert Seedman to diffuse the situation.

One Mosque # 7 member was eventually apprehended and tried, but

ultimately acquitted.[3]

What

was so extraordinary about this 1972 incident was the Muslims’ ability

to leverage their influence to address the situation. Charges were not

brought against anyone from the mosque until two years later,

and the subsequent trial resulted in an acquittal. Further, the Muslims

demanded both “an apology from the city and an all-Black police force

for Harlem.”[4]

The Muslims of Mosque #7 also held a unity rally protesting the police

department’s actions. Sunni Muslims were in attendance, including the

world-renowned Egyptian scholar and Qu’ran reciter Sheikh Mahmoud Khalil

al-Hussary.[5] Muslims of differing theological opinions came together to oppose repressive policing of Muslims and people of color.

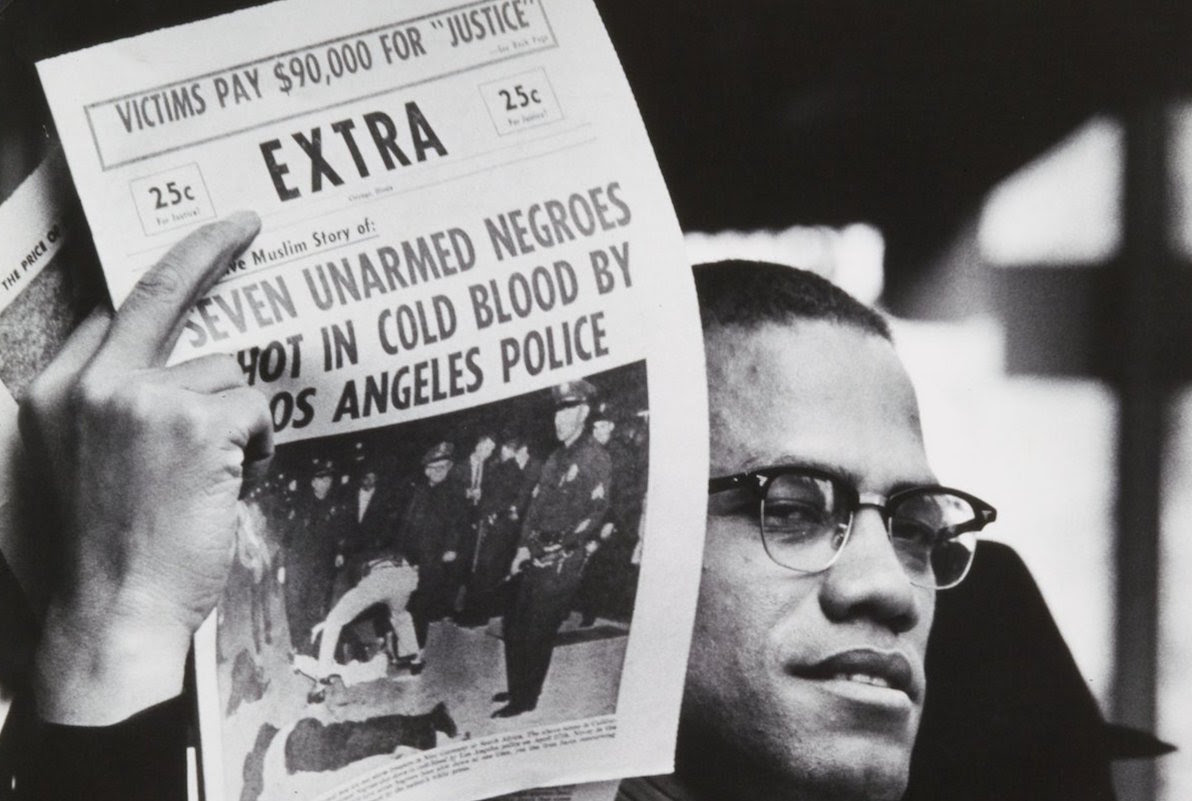

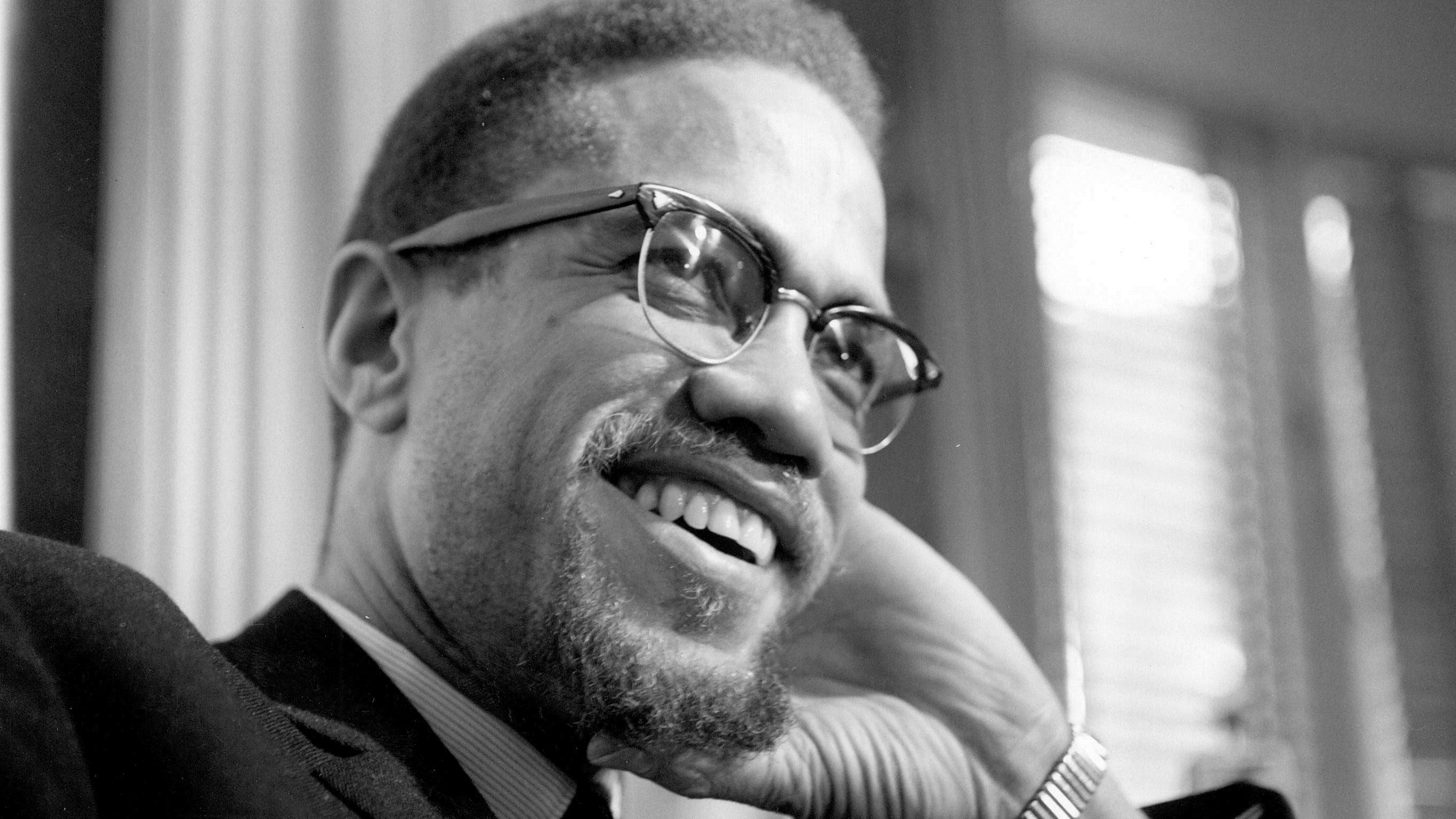

This was not the first time Muslims had fought for police accountability in New York City. If you’ve seen the Spike Lee film Malcolm X (or if you’ve read the explanation of Kanye West’s song Power on rapgenius.com),

then you probably know about Johnson Hinton, a member of the Nation who

was savagely brutalized and arrested after he and two other Muslims

confronted two white police officers for beating a Black man in Harlem

in 1957. Members of the Fruit of Islam, the Nation’s paramilitary-style

self-defense wing, marched orderly to the local police precinct, flanked

by a crowd of roughly five hundred angry Harlemites. In response to

Malcolm X’s leadership in coordinating the Muslims’ efforts on the night

of the beating, one NYPD officer famously exclaimed, “No one man should

have that much power.”[6]

Hinton received medical attention and the largest settlement for a

police brutality case in New York City’s history at that time. Both the

Nation of Islam’s run-in with the police and its ability to apply the

necessary pressure to obtain greater justice for its member were

indicative of the relationship it would develop with the NYPD over the

next decade and a half.

The

Nation’s 1972 call for local control of the police was not atypical.

Black Sunni Muslims in urban American cities pursued similar strategies.

While they may not have mounted campaigns for all-Black police forces,

many initiated efforts to maintain law and order in their own

neighborhoods. One example is the aforementioned Mosque of Islamic

Brotherhood (MIB). The lineal descendent of Malcolm X’s Muslim Mosque

Inc., MIB took Malcolm’s calls for local control to heart. In the late

1960’s, MIB adopted the heroin-infested block of 113th St.

and St. Nicholas Ave. in Harlem, pushing out criminals and drug dealers

and creating the backbone of what quickly became a peaceful, thriving,

and now rapidly gentrifying neighborhood. A later example is Masjid

Taqwa in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. Members of the community

purportedly patrolled their rooftop with scoped rifles in order to

police the neighborhood when the mosque was first built in 1980. As a

result, a roughly two block radius surrounding the mosque is now home to

grocery stores, restaurants, barbershops, and other businesses that

cater to a vibrant community of Muslims, and passersby need not worry

about crime or harassment.

During the 1960’s and 1970’s, Brooklyn’s Yasin Mosque also created a safe zone through the efforts of Ra’d,

its own paramilitary wing, which oversaw the well-being of mosque

members and the surrounding community. As with Mosque # 7, this

sometimes required skirmishes with hostile police officers who came from

outside the community.[7]

Yasin Mosque served as the nucleus for the nation’s largest network of

African American Sunni mosques, the Darul Islam movement – or the Dar

for short. Imam Jamil Al-Amin – formerly known as H. Rap Brown, a

prominent leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

and the Black Panther Party – exported the Dar’s local control model to

Atlanta. There, he and his followers cleaned up the notoriously

crime-ridden West End neighborhood, creating yet another safe zone

policed by Black American Muslims.

What

emerges from this history is a rich tradition of local control and

community policing among Muslim African Americans. While such strategies

varied by context and location, they generally followed a three-part

model. First, community members policed their own neighborhoods,

organically creating safe spaces where businesses, schools, and

community life flourished. Second, these groups created strong

relationships with community-minded elected officials, and Muslims and

people of color in law enforcement, to maintain these spaces.[8]

Third, they leveraged their relationships with members of the broader

community – who were grateful for the Muslims’ contributions to the

community – to engage in protests to ensure police accountability when

necessary.

As the list of Black men and

women killed with impunity by police grows, this history of Black

Muslims’ strategies to foster community control and fight police

brutality is becoming increasingly relevant. The Islamic Society of

North America (ISNA) issued a statement in the wake of the Baltimore

uprising earlier this year. In its response, ISNA demonstrated just how

out of touch the organization was with the community it seeks to

represent.[9]

While our knowledge of the illegal surveillance and harassment of

Muslim communities grows, the links between these current injustices and

the infamous COINTELPRO policies that targeted scores of Black

communities (Muslim and non-Muslim alike) are unknown to many Muslim

Americans. Rediscovering this history carries a serious urgency. As

Islamophobia becomes increasingly widespread, Muslims stand to lose much

of the support and cultural capital they have gained over the course of

the last 50+ years, which came as a result of their efforts to make

life better for working-class communities and people of color. More

importantly, the freedom, security, and lives of millions of American

women and men victimized due to their race and religion is at stake.

Muslims in America are in dire need of the insights provided by the

Black Muslim experience, just as communities of color are in dire need

of the local control strategies that Black Muslims once pioneered.

[1] “Cops Invade Mosque: Editorial Invasion of Mosque No. 7.” New York Amsterdam News (1962-1993); Apr 22, 1972. p. A1.

[2]

Since Mosque # 7 was deemed a “sensitive location”, police established a

protocol stipulating they provide advanced notice if they needed to

search the mosque. In the past, the NYPD was duly granted permission and

entered the premises in a respectful manner.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Russell, Carlos. “A funny thing happened.” New York Amsterdam News (1962-1993); May 6, 1972. p. A5.

[5] Craft, Mona. “Muslims seek unity.” New York Amsterdam News (1962-1993); May 13, 1972. p. B12

[6] Marable, Manning. Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. Reprint edition. New York: Penguin Books, 2011. p. 128

[7] Curtis, R.M. Mukhtar. “The Formation of the Darul Islam Movement.” In Muslim Communities in North America, by Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad and Jane I. Smith. SUNY Press, 1994. 59

[8]

Even the Nation of Islam’s supreme leader, the Honorable Elijah

Muhammad, received an award from the National Society of Afro-American

Policemen in 1969 at a New York City luncheon. Minister Louis Farrakhan

accepted the citation on his behalf. “Farakhan to Accept Citation.” New

York Amsterdam News (1962-1993); June 14, 1969. p. 3.

[9]

For the statement and some of the critiques against it, see:

Contributor, Guest. “MuslimARC – Open Letter to American Muslim

Organizations on Police Brutality, Baltimore and Freddie Gray.” Altmuslim. Accessed May 16, 2015. http://www.patheos.com/blogs/

Rasul Miller

is a PhD student in History and Africana Studies at the University of

Pennsylvania. His research interests include Muslim movements in 20th

century America and their relationship to Black internationalist thought

and West African intellectual history.

|

Friday, 4 August 2017

| by Ahmad zakx othman | on August 4 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Using Gm

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Blacks Islamic History: Blacks Islamic History: MUSLIMS AND JAZZ IN 1953

Blacks Islamic History: Blacks Islamic History: MUSLIMS AND JAZZ IN 1953 : Blacks Islamic History: MUSLIMS AND JAZZ IN 1953 : ...

-

The African Qurʾā n: Ramadan Remedies fo r Racial and Religious Int olerance on July,16, 2017 Qurʾān , Sura Yusuf, 12:3...

-

Conversation A Trajectory of Manumission: Examining the Issue of Slavery in Islam ...

and serve as an active leader in Los Angeles, Calif, and surrounding

communities. This horrible incident parallels the indignities and

injustices that other African American leaders have suffered as a result

of

and serve as an active leader in Los Angeles, Calif, and surrounding

communities. This horrible incident parallels the indignities and

injustices that other African American leaders have suffered as a result

of  removed

mural of Imam Khomeini and Malcolm X, that once faced Masjid Al-Rasul,

LA. Imam Khomeini aligned his teachings with the objectives of the

Prophetic mission of Muhammad (saw) which “was to teach the people the

path to eliminate oppression; to teach the path that would enable the

people to confront the exploiting power.” [1] For Shaykh Abdul-Karim,

establishing this justice aligns with preparing for Imam Mahdi (ajf) who

the Holy Prophet Muhammad (saw) tells us: “After me are Caliphs and

after Caliphs, rulers and after rulers, kings and after kings, emperors

and tyrannical and rebellious dictators. After that a man from my Ahlul

Bayt (a.s.) will reappear and fill the earth with justice and equity

just as it would be fraught with injustice and oppression.” [2] This

mission and legacy is not without its challenges as exhibited by the FBI

raid and the struggles to fund necessary programing costs for the

expansion of the Masjid Al-Rasul Foundation into the Fifth Ward in

Houston, Texas, and more recently, Chicago. Despite these challenges,

MAR proceeds.

removed

mural of Imam Khomeini and Malcolm X, that once faced Masjid Al-Rasul,

LA. Imam Khomeini aligned his teachings with the objectives of the

Prophetic mission of Muhammad (saw) which “was to teach the people the

path to eliminate oppression; to teach the path that would enable the

people to confront the exploiting power.” [1] For Shaykh Abdul-Karim,

establishing this justice aligns with preparing for Imam Mahdi (ajf) who

the Holy Prophet Muhammad (saw) tells us: “After me are Caliphs and

after Caliphs, rulers and after rulers, kings and after kings, emperors

and tyrannical and rebellious dictators. After that a man from my Ahlul

Bayt (a.s.) will reappear and fill the earth with justice and equity

just as it would be fraught with injustice and oppression.” [2] This

mission and legacy is not without its challenges as exhibited by the FBI

raid and the struggles to fund necessary programing costs for the

expansion of the Masjid Al-Rasul Foundation into the Fifth Ward in

Houston, Texas, and more recently, Chicago. Despite these challenges,

MAR proceeds. communities’

unique needs. All three locations of MAR — Los Angeles, Houston, and

Chicago — seek to provide this space and the resources needed to

cultivate the sense of self-awareness that strengthens the souls,

provides nourishment to the bodies and serves truth to the oppressed in

times of rampant anti-Blackness and anti-Islamic sentiment.

communities’

unique needs. All three locations of MAR — Los Angeles, Houston, and

Chicago — seek to provide this space and the resources needed to

cultivate the sense of self-awareness that strengthens the souls,

provides nourishment to the bodies and serves truth to the oppressed in

times of rampant anti-Blackness and anti-Islamic sentiment. limited

educational resources for a largely African American and

Spanish-speaking population were key issues that that the masjid

addresses by offering programs in Spanish and English while also

providing traditional prayer services in Arabic. The Houston masjid was a

sincere labor of love in which Hassan Abdul-Karim took into

consideration both the history and needs of the Fifth Ward community,

once known as the “Bloody 5th”[3] to unite the community with communal

meals, activities such as Islamic movie nights, community clean-up

efforts and sincere da’wah through service.

limited

educational resources for a largely African American and

Spanish-speaking population were key issues that that the masjid

addresses by offering programs in Spanish and English while also

providing traditional prayer services in Arabic. The Houston masjid was a

sincere labor of love in which Hassan Abdul-Karim took into

consideration both the history and needs of the Fifth Ward community,

once known as the “Bloody 5th”[3] to unite the community with communal

meals, activities such as Islamic movie nights, community clean-up

efforts and sincere da’wah through service. twelve years of his life pursuing Islamic Studies in seminaries and

universities in the United States and Iran. In 2005, he earned an MA in

Religious Studies at Duke University before moving to Texas in 2007 to

pursue a PhD in Arabic Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

After a short hiatus, Shaykh Muhibullah resumed PhD studies at the

University of Tehran while also pursuing ijtihad with prominent

Ayatollahs like Waheed Al-Khurasani and Sayyid Kamal Al-Haydari in the

Islamic Seminary of Qom, Iran.

twelve years of his life pursuing Islamic Studies in seminaries and

universities in the United States and Iran. In 2005, he earned an MA in

Religious Studies at Duke University before moving to Texas in 2007 to

pursue a PhD in Arabic Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

After a short hiatus, Shaykh Muhibullah resumed PhD studies at the

University of Tehran while also pursuing ijtihad with prominent

Ayatollahs like Waheed Al-Khurasani and Sayyid Kamal Al-Haydari in the

Islamic Seminary of Qom, Iran.