By AHMAD ZAKX UTHMAN

On 14/09/2017

time:11:47pm

On April 14th, 1972, a man claiming to be a Detective Thomas from New York City’s 28th

police precinct placed a call requesting assistance for a fellow

officer in distress. The call, later determined to be a fake, prompted

two officers to rush to the address, which was the Nation of Islam’s

Harlem Mosque # 7. The two officers “smashed their way into the 116th St. Mosque.”[1] This violated of the NYPD’s policy with regard to the Muslim place of worship.[2]

Members of the mosque felt compelled to protect the sanctity of the

space and the safety of the congregation. A fight broke out. It is

unclear exactly what happened, but in the ensuing melee, Phillip

Cardillo, one of the two officers who had burst into the mosque

unannounced, was killed.

More

officers rushed to the mosque, creating a scene that the Amsterdam News

described as an “attack” and “invasion”. Harlem residents, who saw the

mosque as an essential asset to the community, formed a crowd of

concerned onlookers. Minister Louis Farrakhan, the spiritual leader for

Mosque # 7 at the time, arrived along with Harlem Congressman Charlie

Rangel. Members of the Mosque of Islamic Brotherhood, Harlem’s principal

Sunni Muslim institution, rushed over to help ensure the safety of the

roughly three to five hundred members of Mosque # 7 who were trapped

inside the building. Minister Farrakhan urged the crowd, which had now

grown angry, to keep calm. He and Congressman Rangel worked out a deal

with NYPD’s Chief of Detectives Albert Seedman to diffuse the situation.

One Mosque # 7 member was eventually apprehended and tried, but

ultimately acquitted.[3]

What

was so extraordinary about this 1972 incident was the Muslims’ ability

to leverage their influence to address the situation. Charges were not

brought against anyone from the mosque until two years later,

and the subsequent trial resulted in an acquittal. Further, the Muslims

demanded both “an apology from the city and an all-Black police force

for Harlem.”[4]

The Muslims of Mosque #7 also held a unity rally protesting the police

department’s actions. Sunni Muslims were in attendance, including the

world-renowned Egyptian scholar and Qu’ran reciter Sheikh Mahmoud Khalil

al-Hussary.[5] Muslims of differing theological opinions came together to oppose repressive policing of Muslims and people of color.

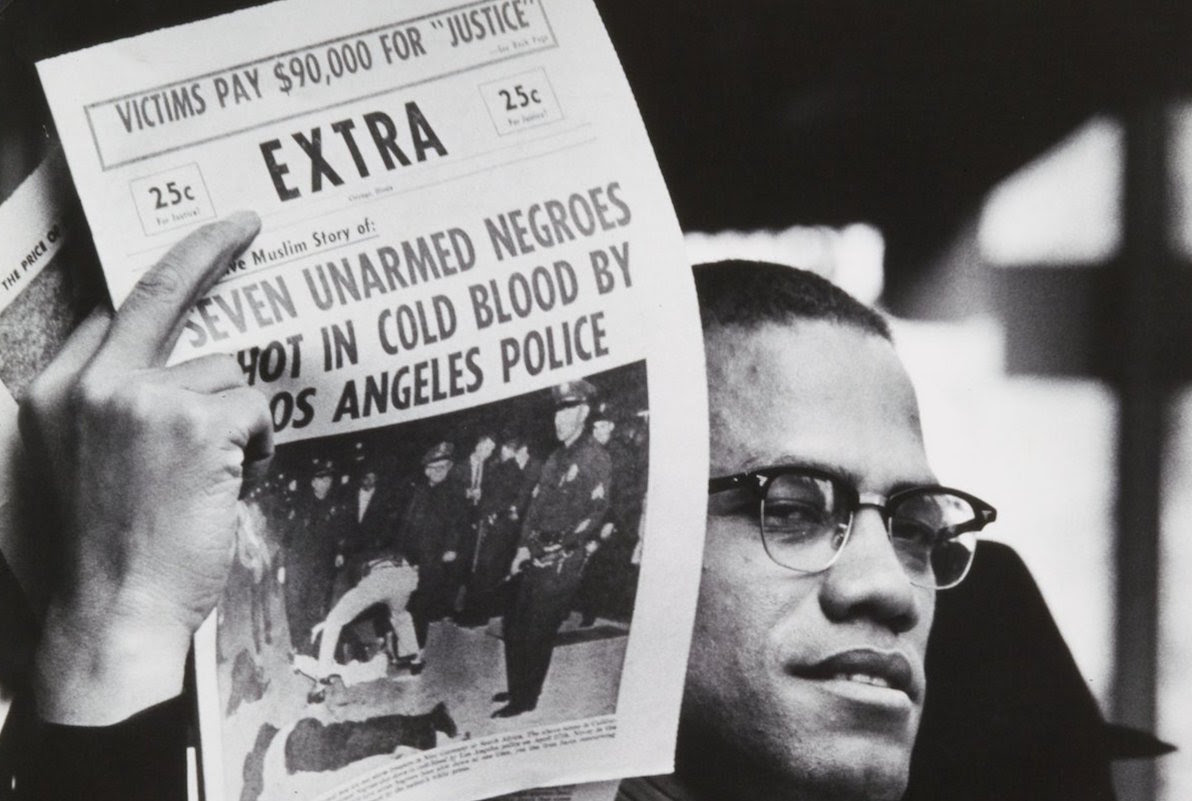

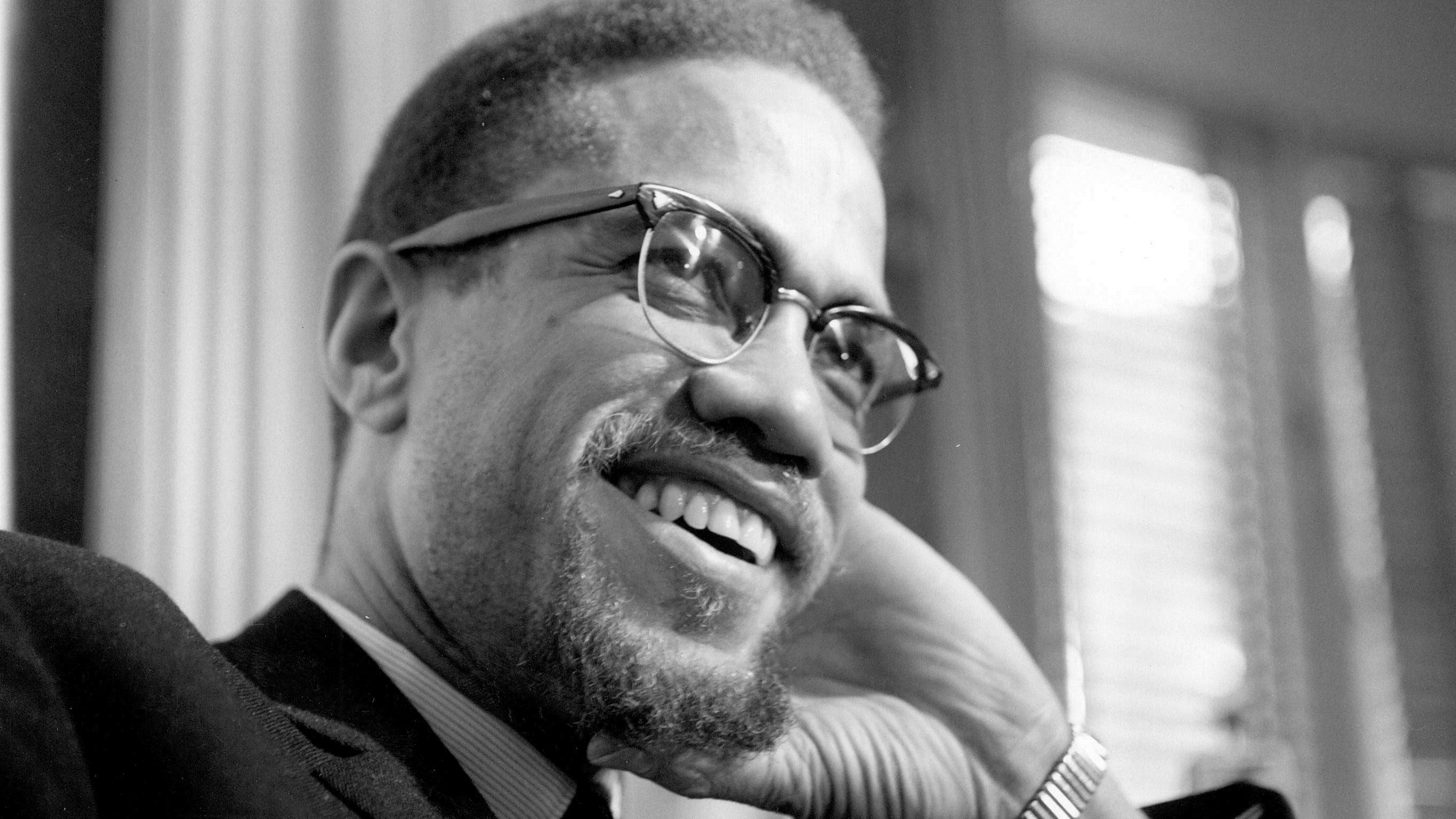

This was not the first time Muslims had fought for police accountability in New York City. If you’ve seen the Spike Lee film Malcolm X (or if you’ve read the explanation of Kanye West’s song Power on rapgenius.com),

then you probably know about Johnson Hinton, a member of the Nation who

was savagely brutalized and arrested after he and two other Muslims

confronted two white police officers for beating a Black man in Harlem

in 1957. Members of the Fruit of Islam, the Nation’s paramilitary-style

self-defense wing, marched orderly to the local police precinct, flanked

by a crowd of roughly five hundred angry Harlemites. In response to

Malcolm X’s leadership in coordinating the Muslims’ efforts on the night

of the beating, one NYPD officer famously exclaimed, “No one man should

have that much power.”[6]

Hinton received medical attention and the largest settlement for a

police brutality case in New York City’s history at that time. Both the

Nation of Islam’s run-in with the police and its ability to apply the

necessary pressure to obtain greater justice for its member were

indicative of the relationship it would develop with the NYPD over the

next decade and a half.

The

Nation’s 1972 call for local control of the police was not atypical.

Black Sunni Muslims in urban American cities pursued similar strategies.

While they may not have mounted campaigns for all-Black police forces,

many initiated efforts to maintain law and order in their own

neighborhoods. One example is the aforementioned Mosque of Islamic

Brotherhood (MIB). The lineal descendent of Malcolm X’s Muslim Mosque

Inc., MIB took Malcolm’s calls for local control to heart. In the late

1960’s, MIB adopted the heroin-infested block of 113th St.

and St. Nicholas Ave. in Harlem, pushing out criminals and drug dealers

and creating the backbone of what quickly became a peaceful, thriving,

and now rapidly gentrifying neighborhood. A later example is Masjid

Taqwa in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. Members of the community

purportedly patrolled their rooftop with scoped rifles in order to

police the neighborhood when the mosque was first built in 1980. As a

result, a roughly two block radius surrounding the mosque is now home to

grocery stores, restaurants, barbershops, and other businesses that

cater to a vibrant community of Muslims, and passersby need not worry

about crime or harassment.

During the 1960’s and 1970’s, Brooklyn’s Yasin Mosque also created a safe zone through the efforts of Ra’d,

its own paramilitary wing, which oversaw the well-being of mosque

members and the surrounding community. As with Mosque # 7, this

sometimes required skirmishes with hostile police officers who came from

outside the community.[7]

Yasin Mosque served as the nucleus for the nation’s largest network of

African American Sunni mosques, the Darul Islam movement – or the Dar

for short. Imam Jamil Al-Amin – formerly known as H. Rap Brown, a

prominent leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

and the Black Panther Party – exported the Dar’s local control model to

Atlanta. There, he and his followers cleaned up the notoriously

crime-ridden West End neighborhood, creating yet another safe zone

policed by Black American Muslims.

What

emerges from this history is a rich tradition of local control and

community policing among Muslim African Americans. While such strategies

varied by context and location, they generally followed a three-part

model. First, community members policed their own neighborhoods,

organically creating safe spaces where businesses, schools, and

community life flourished. Second, these groups created strong

relationships with community-minded elected officials, and Muslims and

people of color in law enforcement, to maintain these spaces.[8]

Third, they leveraged their relationships with members of the broader

community – who were grateful for the Muslims’ contributions to the

community – to engage in protests to ensure police accountability when

necessary.

As the list of Black men and

women killed with impunity by police grows, this history of Black

Muslims’ strategies to foster community control and fight police

brutality is becoming increasingly relevant. The Islamic Society of

North America (ISNA) issued a statement in the wake of the Baltimore

uprising earlier this year. In its response, ISNA demonstrated just how

out of touch the organization was with the community it seeks to

represent.[9]

While our knowledge of the illegal surveillance and harassment of

Muslim communities grows, the links between these current injustices and

the infamous COINTELPRO policies that targeted scores of Black

communities (Muslim and non-Muslim alike) are unknown to many Muslim

Americans. Rediscovering this history carries a serious urgency. As

Islamophobia becomes increasingly widespread, Muslims stand to lose much

of the support and cultural capital they have gained over the course of

the last 50+ years, which came as a result of their efforts to make

life better for working-class communities and people of color. More

importantly, the freedom, security, and lives of millions of American

women and men victimized due to their race and religion is at stake.

Muslims in America are in dire need of the insights provided by the

Black Muslim experience, just as communities of color are in dire need

of the local control strategies that Black Muslims once pioneered.

[1] “Cops Invade Mosque: Editorial Invasion of Mosque No. 7.” New York Amsterdam News (1962-1993); Apr 22, 1972. p. A1.

[2]

Since Mosque # 7 was deemed a “sensitive location”, police established a

protocol stipulating they provide advanced notice if they needed to

search the mosque. In the past, the NYPD was duly granted permission and

entered the premises in a respectful manner.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Russell, Carlos. “A funny thing happened.” New York Amsterdam News (1962-1993); May 6, 1972. p. A5.

[5] Craft, Mona. “Muslims seek unity.” New York Amsterdam News (1962-1993); May 13, 1972. p. B12

[6] Marable, Manning. Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. Reprint edition. New York: Penguin Books, 2011. p. 128

[7] Curtis, R.M. Mukhtar. “The Formation of the Darul Islam Movement.” In Muslim Communities in North America, by Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad and Jane I. Smith. SUNY Press, 1994. 59

[8]

Even the Nation of Islam’s supreme leader, the Honorable Elijah

Muhammad, received an award from the National Society of Afro-American

Policemen in 1969 at a New York City luncheon. Minister Louis Farrakhan

accepted the citation on his behalf. “Farakhan to Accept Citation.” New

York Amsterdam News (1962-1993); June 14, 1969. p. 3.

[9]

For the statement and some of the critiques against it, see:

Contributor, Guest. “MuslimARC – Open Letter to American Muslim

Organizations on Police Brutality, Baltimore and Freddie Gray.” Altmuslim. Accessed May 16, 2015. http://www.patheos.com/blogs/

Rasul Miller

is a PhD student in History and Africana Studies at the University of

Pennsylvania. His research interests include Muslim movements in 20th

century America and their relationship to Black internationalist thought

and West African intellectual history.

|

Thursday, 14 September 2017

Friday, 4 August 2017

| by Ahmad zakx othman | on August 4 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Using Gm

Tuesday, 20 June 2017

|

During

the twentieth century, Islam and Muslims came to enjoy a largely

positive reputation among Black communities throughout the country,

particularly in urban centers. This was a byproduct of the increased

visibility of Black American Muslims in these communities as various

kinds of Islamic religious movements grew in popularity from the 1950s

onward. This trend was also fostered by the efforts of Black Muslim

congregations to address some of the social, political economic and

psycho-spiritual problems that Black Americans faced in an American

society marked by violent anti-Black racism and systematic inequality.

Black Muslims and other Black Americans sympathetic to the Muslim faith

often cited the long history of Islam on the African continent as

indicative of Islam’s status as a more affirming and empowering religion

for Black people, especially in comparison to Christianity. However,

not everyone shared these sentiments.

During

the 1970s and 1980s, a particularly anti-Islamic strand of Black

cultural nationalism began to emerge within the broader cultural and

intellectual movement known as Afrocentrism.[1]

Black intellectuals influenced by this line of thinking depicted Islam

as a religion that was foreign to Africa and brought there by Arab

invaders. They

further held that Muslim attitudes toward race and slavery historically

rendered the religion no less complicit in the oppression of Black

people than that of the Western European Christians who colonized Africa and the Americas. Some non-Black, western educated academics share this historical analysis. Recent publications like Chouki El-Hamel’s Black Morocco and Bruce Hall’s A History of Race in Muslim West Africa

take this critique of Islam’s racial track record a step further by

attributing modern notions of racial difference and anti-Blackness to

precolonial Muslim societies on the African continent. This approach

goes against that of earlier scholars, and thus marks a major shift in

the way ethnic difference in the premodern world is depicted. Recent

years have also witnessed a resurgence in the popularity of this strain

of Afrocentrism among Black popular intellectuals, sometimes referred to

somewhat derisively as “hoteps.” In this article, I will attempt to

explain the rise in popularity of an anti-Islamic brand of Afrocentrism

during the 1970s and 1980s, and the political projects of certain

scholars who played a key role in promoting it. I will also challenge

the reliability of the historical narrative these scholars advanced,

particularly with regard to Islam’s relationship to the societies of

West and Central Africa.

Chancellor Williams and the Emergence of Anti-Muslim Afrocentrism

In

charting the anti-Muslim strain within Afrocentric thought, it is

helpful to begin with the publication of Chancellor Williams’ The Destruction of Black Civilization in 1974.

This work became a mainstay in Afrocentric circles and was used in some

Black Studies college curricula. However, the book was later criticized

by scholars who argued that it was filled with historical inaccuracies and unsubstantiated assertions.

Throughout the book, Williams refers to “white Arabs” and asserts that

color diversity among Arab peoples was due to a history of Arab slavery

similar to European slavery in the Atlantic world. He contends that,

“Blacks are in Arabia for precisely the same reasons Blacks are in the

United States, South America, and the Caribbean Islands—through capture

and enslavement.”[2]

He further projects American notions and histories of race on the

premodern Arab and African worlds, referring to brown skinned Arabs as

“mulattoes.” Williams’ treatment is rife with reifications and

contradictions. But what is perhaps most notable is the degree to which

Williams’ depiction of the relationship between Islam departs from that

of earlier scholars like Frank Snowden and Cheikh Anta Diop, both of

whom also figure prominently in Black Studies cannons. Snowden’s 1970

work Blacks in Antiquity makes the competing claim that modern

notions of race and racial hierarchy did not exist in the premodern

world, even while various forms of ethnocentrism did. Snowden criticized many Afrocentric scholars

including pioneering Senegalese historian and anthropologist Cheikh

Anta Diop, challenging their views on the racial identity of members of

premodern Mediterranean and North African societies.[3]

However, even Diop’s analysis differs greatly from Williams’ with

regard to the relationship between Islam and Africa. According to Diop,

the notion that Islam was intrinsically foreign to African societies

south of the Sahara, or that Islam’s presence in the region was due to

conquest and forced conversion was simply false. Diop famously observed

that, “[m]uch has been made of Arab invasions of Africa: they occurred

in the North, but in Black Africa they are figments of the imagination.”[4]

So what led Williams to construct a competing historical narrative? An observation made in the early chapters of Destruction of Black Civilization

may offer a clue. Williams charges that, “Blacks in the United States

seem to be more mixed up and confused over the search for racial

identity than anywhere else. Hence, many are dropping their white

western slavemasters' names and adopting, not African, but their Arab

and Berber slavemasters' names!”[5]

Williams, who was a practicing Christian, did not absolve European

Christians of guilt in perpetuating the institution of slavery and the

ideology of white supremacy at the expense of people of African descent.

However, he reserved some of his staunchest criticism for

Muslims—leading him to speak, at times, in absolutes and hyperbole, such

as when he called the Egyptian ruler Muhammad Ali “the greatest

murderer of Blacks that ever set foot on the African continent.”[6]

Williams’ seems to take issue with the rising popularity of Islam among

Black Americans. For him, the true project of liberation would be

served by embracing an “African” identity that was decidedly non-Muslim,

making him more apt to celebrate the rulers and resistance movements of

Central African societies like Angola and the Congo. The summaries on

the dust jacket of Destruction of Black Civilization even include a relevant criticism attributed to the Muhammad Speaks newspaper. After praising aspects of the book, the unidentified Muhammad Speaks

representative observes that, “(Williams’) claim that Islam helped the

slavery of Black Africa is untrue because he used white text rather than

accounts of non-whites academia and the truth.” Although the biases of

the flagship publication of the Nation of Islam might seem obvious,

Williams’ was indeed espousing a view that aligned with some notable

white colleagues.

The Orientalist Origins of Anti-Muslim African Historiography

The

practice of disassociating Islam from Africa in spite of its

1,000-year-old history on the continent was not without precedent. Other

notable white scholars exhibited the same tendency. The even more

brazen tactic of attributing to Arabized North Africans the

anti-Blackness of European colonialism was largely pioneered and

popularized by the noted British American historian Bernard Lewis.

Lewis, like Williams, was forthright about his consternation over Black

Americans’ growing embrace of Islam. In this regard, he expresses his

frustration specifically with the twentieth century’s most visible

theorist and proponent of Islam among Black Americans, Malcolm X. After

praising Malcolm X as “an acute and sensitive observer” exhibiting the

“inevitably heightened perceptions of an American black” with regard to

issues of race, he argues that his Islamic faith “prevented him from

realizing the full implications of what he saw” during his travels to

the Middle East.[7]

Lewis goes on to suggests that the racial dynamics of the precolonial

Muslim world were comparable to those of segregationists Alabama. A wide

range of scholars writing on Islam, including John Hunwick, Bruce

Hall, and Richard Brent Turner, have presumed Lewis’ claim to be both

true and universal. As a result, they applied his dubious

characterization of racial dynamics in premodern Muslim societies to

precolonial West Africa. Other historians of West Africa have

demonstrated that, with regard to Muslim West Africa, such depictions

are simply false.

In

a working paper by Africanist historians Alden Young and Karen

Wietzberg entitled “Does Race Have a Global History,” the authors place

Lewis’ work within its proper political context.

“Written

in the aftermath of the Six Day War, this work argued that racism was

endemic to the Islamic world. Lewis produced this work, he acknowledged,

in order to counter what he saw as the pernicious myths of Arnold

Toynbee and Malcolm X that color prejudices were unknown to the Islamic

world. Lewis, whose work was shaped by the geopolitics of the Cold War,

became one of the most widely cited authors on the topic of slavery and

race in Muslim societies.”

Lewis’

status as a Cold Warrior was something he did not deny. At times, he

was quite transparent about his political positionality, such as in his

exchanges with Edward Said in the New York Review of Books. Lewis

does not challenge, for example, Said’s assertion that his scholarship

is motivated by his political stance for increased American military

support of Israel, and his resulting desire to undermine the cause of

Pan-Arabism. Rather, he challenges Said to come clean about his own

political agenda.[8]

In

an article partly concerned with tracing the same intellectual

genealogy that I consider here, the political scientist Hisham Aidi

asks, “[h]ow did Arabs transmute, almost overnight, from being seen by

African-Americans as allies in the struggle against Western racism to a

slave-trading ‘intruder race’ occupying Africa? How did the pro-Arab

pan-Africanism of Malcolm X lose out to the anti-Arab black nationalism

of [Molefi] Asante, Williams and [Wole] Soyinka?”[9]

Indeed, Malcolm X’s embrace and articulation of a politics of Third

World Internationalism, and the growing support of many Black Americans

for Palestinian and North African revolutionary movements that he helped

to foster were very much at odds with Lewis’ political aims. Lewis’

historical representation of race in Muslim societies, augmented by

Afrocentric scholars like Williams and others, would go on to have a

huge impact on both popular and scholarly notions about the relationship

between Islam and anti-Blackness.

Conclusion: Using Black History to Inform Black Islam

Many influential scholars cite Bernard Lewis in their treatments of racial prejudice in the Arabic speaking world.[10]

They extend his analysis to the African continent, taking Lewis’

assertions as objective and representative of Islam around the globe.

They do not consider how categories of race in Africa and the Arabic

speaking world were altered by colonization, Euro-American slavery, and

the rise of Western imperialism. For example, precolonial historical

chronicles reveal that Turkish slaves could be purchased in the West

African city of Timbuktu, and Europeans faced the threat of being

enslaved in North Africa until well into the nineteenth century. These

realities are inconsistent with the historical narrative offered by

Orientalist scholars (like Bernard Lewis) and Afrocentric scholars (like

Chancellor Williams) alike, both of whom would have us believe that

African Muslim societies subjugated African people. By obscuring this

history and the transformations that led to the increased association of

Blackness with slavery during the trans-Atlantic slave trade, these

authors paint a picture that gives the impression that anti-Blackness is

primordial—anachronistically locating its origins in the ancient world.

Conversely, Afrocentricity and Islam can be easily reconciled through

the more accurate historical narratives of scholars like Diop and

Snowden, as well as more recent historians of Africa like Humphrey

Fisher and Rudolph Ware among others. These scholars recognize that

Euro-American slavery and colonization changed how Africa and its people

were perceived and treated around the world. Before these shifts, Islam

was simply one of the various religions that African people freely

embraced, finding it both compelling and affirming. This is the

historical perspective that gave rise to the anti-colonial

Pan-Africanism articulated by Malcolm X and other Black American

radicals who built solidarity with people of the Third World. In light

of this historical perspective, Afrocentricity and Islam need not be at

odds.

[1]

In this article, I use the term Afrocentrism in the broadest possible

manner, referring to a cultural and intellectual orientation that

centers the history and experiences of people of African descent and

seeks to address mechanisms that disenfranchise those people. This is

how I have encountered the term in non-academic circles, though it is

often defined more narrowly than this by academics.

[2] Williams, Chancellor. The Destruction of Black Civilization: Great Issues of a Race from 4500 B.C. to 2000 A.D. Chicago, Ill: Third World, 1974. p. 23

[3] Snowden, Frank. "Misconceptions about African Blacks in the Ancient Mediterranean World: Specialists and Afrocentrists." Arion, Third Series, Vol. 4, No. 3 (Winter, 1997), p. 28-50

[4] Diop, Cheikh Anta. Precolonial

Black Africa: A Comparative Study of the Political and Social Systems

of Europe and Black Africa, from Antiquity to the Formation of Modern

States. Chicago: Lawrence Hill, 1987. p. 101-102

[5] Williams, Chancellor. The Destruction of Black Civilization: Great Issues of a Race from 4500 B.C. to 2000 A.D. Chicago, Ill: Third World, 1974. p. 23

[6] Ibid., p. 159.

[7]Bernard Lewis, Race and Color in Islam.New York: Harper and Row, 1971. p. 3.

[8] Bernard Lewis, “The Question of Orientalism,” The New York Review of Books 29: 11 (1982) and the responses Bernard Lewis, Edward Said and a reply by Oleg Grabar, “Orientalism: An Exchange,” The New York Review of Books 29:13 (1982).

[9]Aidi,

Hisham. "Slavery, Genocide and the Politics of Outrage Understanding

the New Racial Olympics." Slavery, Genocide and the Politics of Outrage |

Middle East Research and Information Project. Middle East Research and

Information Project, n.d. Web

[10]Chouki El Hamel, Black Morocco: A History of Slavery, Race, and Islam.Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013. p. 297.

Rasul Miller is

a PhD student in History and Africana Studies at the University of

Pennsylvania. His research interests include Muslim movements in 20th

century America and their relationship to Black internationalist thought

and West African intellectual history.

|

Saturday, 17 June 2017

Blacks Islamic History: A Trajectory of Manumission: Examining the Issue o...

Blacks Islamic History: A Trajectory of Manumission: Examining the Issue o...: Conversation A Trajectory of Manumission: Examining the Issue of Slavery in Islam ...

Blacks Islamic History: The African Qurʾā n: Ramadan Remedies fo r Racial ...

Blacks Islamic History: The African Qurʾā n: Ramadan Remedies fo r Racial ...: The African Qurʾā n: Ramadan Remedies for Racial and Religious Intolerance on July,16, 2017 Qurʾān , Sura Yusuf, 12:3...

The African Qurʾā

n: Ramadan

Remedies fo

r Racial and

Religious Int

olerance

on July,16, 2017

Qurʾān , Sura Yusuf, 12:3

“The night of my Ascent, I saw Moses who was a Tall brown-

skinned, kinky-haired man.”

Authentic Saying of the Prophet, Saḥīḥ Bukhāri, 462

The Qurʾān, as a rule, is colorblind. It is the Universal Book.

God cares about hearts and deeds, not skin color and hair texture. So

the Qurʾān, unlike other Holy books, lacks racial markers. The only

partial exception to this is the specification that the first human, Ādam (as)—whose name meant black in old Arabic—was formed from fermented black clay. Given Ādam’s

origins maybe we shouldn’t be surprised that many (probably most) of

the tales of the Prophets in the Qurʾān take place in Africa, or that

Black folks figure prominently even in stories set outside the

continent. The narratives of Joseph and Moses, Abraham and Hagar and

Solomon and Sheba, along with countless others, lead us back to Ancient

Africa, and especially the Nile Valley. The modern disciplines of

African history, archaeology, linguistics, and anthropology all show

that the progenitors of Egyptian civilization were—in today’s

terms—black, and that Egypt’s civilization came from inner African

sources. Too bad Hollywood didn’t get the memo!

But an African Qurʾān? Some will say that there is no such thing. However, I argue that the Qurʾān is African because it speaks of Black people and because Africans have recited, taught and lived it in ways that can be instructive to us in America. But most importantly, I will argue that the Qurʾān is a book that speaks to Black people because it speaks to all people. Surah Luqman, a chapter named for a black man, reminds us of the Qurʾān’s vision of a common origin and destiny for humanity: “The creation of all of you—and your resurrection—are as a single soul. Indeed God is Hearing, Seeing” (Q 31:28)

Black People in the life of the Prophet and the Spread of Islam in Africa

Unlike the Qurʾān , The Prophet did sometimes speak of skin color or hair texture—as when he mentioned Musa’s black skin. For many medieval scholars Musa’s blackness (and the blackness of the Egyptians) was so obvious they mentioned it only in passing. For Qurtubi “Musa was extremely dark brown in skin color (asmar shadid al-asmara).” Remember in Sura Ta Ha when Moses puts his hand inside his shirt and it comes out white without illness? (Q 20:23) The Tafsir of the two Jalals (al-Suyuti and al-Mahalli) says it emerged white, “and not its normal dark color.” The famous historian al-Tabari was more blunt still: “According to what was related to us, Moses was black-skinned and God made Musa’s hand turning white, without being stricken by leprosy, a sign for him.”

The life of the Prophet—is full of Black people as well. His last spouse, Mariya was an Egyptian woman, and perhaps to honor his illustrious ancestor who became the father of the Arabs by his marriage to an Ancient Egyptian, he named their son—who passed away in infancy—Ibrahim. Bilal—a freed slave—was likely the second adult male to accept Islam after Abu Bakr (r). When he climbed atop the House of God to call the prayer it signaled to Quraysh the social revolution that was possible in the new religion—turning their world upside down.

Decades later when Arab armies brought Islam forth from its cradle in Arabia, conquering much of the known world, they did not conquer sub-Saharan Africa. In 652 CE Nubian archers stopped their march down the Nile and the Muslims signed a mutual non-aggression treaty. In sub-Saharan West Africa, where the Empire of Ghana controlled much of the world’s medieval gold trade, here too the army was unconquerable. Medieval Arabic sources claim that the Emperor of Ghana could put 100,000 soldiers in the battlefield, 40,000 of them archers. No armed Arab conquest brought Islam to sub-Saharan Africa where one-in-six of the world’s Muslims now reside.

Rather, teachers and clerics were the primary agents in spreading the faith. From towns like Jakha in what is now Mali, the Jakhanke and other African clerical clans traveled as merchants, farmers, and scholars into all the countries of the African west, often as Muslim minorities among non-Muslim populations. Over the course of time, they were instrumental in peacefully converting populations from Senegal in the west to Niger in the east, from Mali in the north to Ghana in the south. Local, indigenous West African populations voluntary accepted the new religion, and some families came to specialize in teaching the Qurʾān and the sciences of Islam. In Part Four, I will discuss the unique Jakhanke approach to the Qurʾān, and its particular relevance for Black Americans.

To conclude, let me be clear: focusing on Africans in the Qurʾān and the Qurʾān in Africa should not cause us to replace one ethnocentrism with another. Sura Maryam reminds us that prophethood was not the monopoly of the children of Israel or any other tribe. God’s teachers do not belong to one people, but to all people.

After mentioning Enoch, Abraham, Ishmael, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Zachary, John, and Jesus (upon them peace) all in a single Sura, God reminds us in a single aya that the blessed teachers of His word were from (and for) all the children of Adam and Eve:

These are some of the Prophets whom God has blessed from Adam’s progeny, and from those We carried with Noah, and from the progeny of Abraham and Israel, and from those whom We guided and elected. When the signs of the Merciful were recited to them, they fell down prostrate and wept. (Q 19:58)The Qurʾān reminds us that God’s glory should leave us humbled. Claiming a monopoly on God, on the other hand, reveals pride, arrogance, and haughtiness (kibr, istikbar, takabbur). Indeed, as African American Muslims we know Black supremacy as creed is a theological dead end. Rather, by positing an African Qurʾān, my goal is to use Qurʾān as Furqān—criteria for understanding—to help undo the damage centuries of racial

and religious intolerance have wrought. In Part Two of theAfrican Qurʾān, I will discuss the causes and cures for intolerance through a discussion of the third juz of the Qur’an.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Blacks Islamic History: Blacks Islamic History: MUSLIMS AND JAZZ IN 1953

Blacks Islamic History: Blacks Islamic History: MUSLIMS AND JAZZ IN 1953 : Blacks Islamic History: MUSLIMS AND JAZZ IN 1953 : ...

-

Conversation A Trajectory of Manumission: Examining the Issue of Slavery in Islam ...

-

The African Qurʾā n: Ramadan Remedies fo r Racial and Religious Int olerance on July,16, 2017 Qurʾān , Sura Yusuf, 12:3...

and serve as an active leader in Los Angeles, Calif, and surrounding

communities. This horrible incident parallels the indignities and

injustices that other African American leaders have suffered as a result

of

and serve as an active leader in Los Angeles, Calif, and surrounding

communities. This horrible incident parallels the indignities and

injustices that other African American leaders have suffered as a result

of  removed

mural of Imam Khomeini and Malcolm X, that once faced Masjid Al-Rasul,

LA. Imam Khomeini aligned his teachings with the objectives of the

Prophetic mission of Muhammad (saw) which “was to teach the people the

path to eliminate oppression; to teach the path that would enable the

people to confront the exploiting power.” [1] For Shaykh Abdul-Karim,

establishing this justice aligns with preparing for Imam Mahdi (ajf) who

the Holy Prophet Muhammad (saw) tells us: “After me are Caliphs and

after Caliphs, rulers and after rulers, kings and after kings, emperors

and tyrannical and rebellious dictators. After that a man from my Ahlul

Bayt (a.s.) will reappear and fill the earth with justice and equity

just as it would be fraught with injustice and oppression.” [2] This

mission and legacy is not without its challenges as exhibited by the FBI

raid and the struggles to fund necessary programing costs for the

expansion of the Masjid Al-Rasul Foundation into the Fifth Ward in

Houston, Texas, and more recently, Chicago. Despite these challenges,

MAR proceeds.

removed

mural of Imam Khomeini and Malcolm X, that once faced Masjid Al-Rasul,

LA. Imam Khomeini aligned his teachings with the objectives of the

Prophetic mission of Muhammad (saw) which “was to teach the people the

path to eliminate oppression; to teach the path that would enable the

people to confront the exploiting power.” [1] For Shaykh Abdul-Karim,

establishing this justice aligns with preparing for Imam Mahdi (ajf) who

the Holy Prophet Muhammad (saw) tells us: “After me are Caliphs and

after Caliphs, rulers and after rulers, kings and after kings, emperors

and tyrannical and rebellious dictators. After that a man from my Ahlul

Bayt (a.s.) will reappear and fill the earth with justice and equity

just as it would be fraught with injustice and oppression.” [2] This

mission and legacy is not without its challenges as exhibited by the FBI

raid and the struggles to fund necessary programing costs for the

expansion of the Masjid Al-Rasul Foundation into the Fifth Ward in

Houston, Texas, and more recently, Chicago. Despite these challenges,

MAR proceeds. communities’

unique needs. All three locations of MAR — Los Angeles, Houston, and

Chicago — seek to provide this space and the resources needed to

cultivate the sense of self-awareness that strengthens the souls,

provides nourishment to the bodies and serves truth to the oppressed in

times of rampant anti-Blackness and anti-Islamic sentiment.

communities’

unique needs. All three locations of MAR — Los Angeles, Houston, and

Chicago — seek to provide this space and the resources needed to

cultivate the sense of self-awareness that strengthens the souls,

provides nourishment to the bodies and serves truth to the oppressed in

times of rampant anti-Blackness and anti-Islamic sentiment. limited

educational resources for a largely African American and

Spanish-speaking population were key issues that that the masjid

addresses by offering programs in Spanish and English while also

providing traditional prayer services in Arabic. The Houston masjid was a

sincere labor of love in which Hassan Abdul-Karim took into

consideration both the history and needs of the Fifth Ward community,

once known as the “Bloody 5th”[3] to unite the community with communal

meals, activities such as Islamic movie nights, community clean-up

efforts and sincere da’wah through service.

limited

educational resources for a largely African American and

Spanish-speaking population were key issues that that the masjid

addresses by offering programs in Spanish and English while also

providing traditional prayer services in Arabic. The Houston masjid was a

sincere labor of love in which Hassan Abdul-Karim took into

consideration both the history and needs of the Fifth Ward community,

once known as the “Bloody 5th”[3] to unite the community with communal

meals, activities such as Islamic movie nights, community clean-up

efforts and sincere da’wah through service. twelve years of his life pursuing Islamic Studies in seminaries and

universities in the United States and Iran. In 2005, he earned an MA in

Religious Studies at Duke University before moving to Texas in 2007 to

pursue a PhD in Arabic Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

After a short hiatus, Shaykh Muhibullah resumed PhD studies at the

University of Tehran while also pursuing ijtihad with prominent

Ayatollahs like Waheed Al-Khurasani and Sayyid Kamal Al-Haydari in the

Islamic Seminary of Qom, Iran.

twelve years of his life pursuing Islamic Studies in seminaries and

universities in the United States and Iran. In 2005, he earned an MA in

Religious Studies at Duke University before moving to Texas in 2007 to

pursue a PhD in Arabic Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

After a short hiatus, Shaykh Muhibullah resumed PhD studies at the

University of Tehran while also pursuing ijtihad with prominent

Ayatollahs like Waheed Al-Khurasani and Sayyid Kamal Al-Haydari in the

Islamic Seminary of Qom, Iran.