A

number of years ago I gave a lecture on Swahili coast history to a

group of educators and students on Chicago’s South Side. During the

Q&A period one older gentleman asked me why I didn’t say more about

Muslim-led slavery of Africans in the Indian Ocean. I responded somewhat

inadequately that slavery in the Indian Ocean wasn’t a religious issue

but an economic one. The gentleman wasn’t satisfied, explaining that he

was disappointed in Louis Farrakhan’s silence on the issue and

testifying to the continuing presence of slavery in African Muslim

countries like Mauritania to this day, explaining that slavery was

justified by sharia.

The

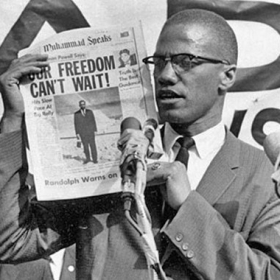

man in question was not a conservative Christian, nor part of

Islamophobia Inc. but rather part of a generation of Afrocentric black

nationalists in the intellectual tradition of John Henrik Clarke.

He was condemning the practice of slavery globally from his commitment

to Afrocentrism and part of the broader tradition of black nationalist

liberation politics in in the United States. He wondered why Muslims

were seemingly behind in that fight or ambivalent to the practice of

enslavement. In spite of my historical understanding of slavery and the

slave trade as practices that many non-Muslim African as well as Muslim

African societies often willingly engaged in, his words forced me to

reckon more seriously with how Islamic law treats the abolition of

slavery. I am especially interested in this issue as someone trained as a

historian of East Africa, where the abolitionist movement predated and

then became part of the first wave of European colonization of Africa,

post 1885. My position is that the Islamic tradition has already

developed an abolitionist ethos and a strong commitment to liberation,

out of a set of social and political struggles, including resistance to

European colonialism, that took place in the historical encounters

between Islam, Africa and the West in the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries.

Afrocentrists

often point to the Quran and Hadith’s sanction of slavery. It is true

that Islam accepted slavery as a part of Arabian society, but there is

no evidence the tradition actively encouraged the taking of slaves. If

one wishes to speak of a particular ‘trajectory’ of Islamic

interpretation based on the Qur'an and Sunnah, it is a trajectory of

manumission, not abolition.1

The Prophet Muhammad assumed that if manumission continued to regularly

occur, then slavery could continue to exist without being a

trans-generational status, and would eventually die out.

The

Prophet Muhammad challenged the practice of slavery in Arabian society

by compelling the powerful to care for and protect the less powerful.2

If masters and slaves could share some basic moral assumptions,

powerful masters would feel a social obligation to protect and show

kindness to their slaves. In Islam this is exemplified by a hadith

enjoining the believer to treat their slaves as they would treat their

own children.3 Slaves in Islam would (ideally) function more like kin and less like a separate caste of sub-humans.4

Their offspring, again ideally, would be free to assume their place

alongside the freeborn. None of these reforms radically challenged the

‘natural’ reality of slavery itself.5

Why

didn’t Muslims abolish slavery earlier? This is a valid question and it

is worth it for Muslims to reflect very hard and critically about,

especially if one is seriously committed to practicing the tradition.

But when Afrocentrists ask Muslims why Islam did not abolish slavery,

there is a hidden assumption that non-Muslim African societies had

already abolished the practice. But in fact many powerful non-Muslim

African societies depended on slavery for their wealth and resented

European imposed abolition for that reason, for instance, the Asante

empire of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Abolition

as an ethical dilemma only occurs because we inhabit a very different

time from the early Muslims, as well as most pre-colonial African

societies. We often forget that for Jesus, Muhammad and other moral

teachers of the past, the master-slave relationship was both a fact of

life and a metaphor of our relationship with the Divine.6

The more relevant question then, is not ‘why didn’t Muslims abolish

slavery?’, but ‘what makes our time different from the time of the early

Muslims?’

One

possible answer to that question is that we now live in a global

society where we take the freedom of an individual as an irrevocable

human right. Although this ideal is often traced to Western origins, it

is important to note that it has other global, non-Western genealogies

that are both Muslim and African. Haitian

revolutionaries, among whom were African Muslims, were first among

those insisting on this freedom in their struggle to end slavery in the

late 1700s. At around the same time, the West African Muslim ruler Abdul

Kader Kane sought to abolish the slave trade in his realm, in order to

protect his subjects from the French-controlled slave trade at Saint

Louis.7

Formerly

enslaved Muslims also helped to reshape community perceptions of

slavery. In East Africa especially, the abolition of slavery coincided

with the new popularity of Sufi brotherhoods as tools for the mass

propagation of Islam. Sufism became the language by which formerly

servile people appropriated the message of Islam to undermine the ijma

around the social status of slaves and ex-slaves. In Lamu, Kenya, the

'Alawi shaykh Habib Saleh angered the town's former slaveholding elite

by teaching ex-slaves. In Bagamoyo,

Tanzania, an ex-slave from the Congo rose to become a Sufi shaykh and

one of the most knowledgeable scholars of the region; he faced strong

opposition from former slave owners.8

The first five decades of the twentieth century in Africa revealed

Muslims reshaping the consensus on slavery. This process of reshaping ijma

was not only an elite scholarly one; it included formerly enslaved

Muslims, who contested their rights within the idioms of Islam, molding

Islamic cultural repertoires to critique the exclusionary social

practices of Muslim elites.

Traditions,

Islam included, are not closed caskets but open conversations and

debates often characterized by shifting notions of what is permissible.

Slavery is one such shifting notion. There is nothing in the Islamic

tradition mandating slavery. Thus, the overwhelming majority of Muslims

today find slavery distasteful and have no desire to practice it. They

have internalized a desire not to own people that is very modern. This

is a direct result of the most oppressed and vulnerable elements of

human global society forcing the world to accept a more robust and

inclusive concept of individual freedom. Concepts of abolition and

freedom are the product of centuries of struggle by enslaved Africans

and others to radicalize and decolonize the values of the societies they

found themselves forcibly dragged into. They constitute a valuable tool

that a range of activists today, from the Rabaa Square protests in

Egypt to the garment worker strikes in Bangladesh to Black Lives Matter

activists in the US, use to launch more radical critiques of global

inequality, exploitation, and other conditions analogous to slavery.

The

Prophet Muhammad’s attempt to protect the enslaved and to grant them

protections and rights, without abolishing slavery, was not a moral

failing, but the advancement to the limits of what it was possible to

envision within his era. If we do not acknowledge this, we will continue

to reproduce two stale arguments of past Muslim apologists: that

abolition is a Western concept that fetishizes consent and freedom, or

that the Prophet Muhammad was an abolitionist. Neither of these are

tenable positions, and there are severe moral costs to holding them,

that compromise the moral compass of Muslims and leave serious and

inquisitive outsiders with a suspicion that Muslims are more interested

in theological apologetics than an honest reckoning with history. For

instance, it is but a short step from the saying abolition is a Western

concept to making the argument, like the late Islamist philosopher Abu

Ala Mawdudi, that we need to retain slavery as a mark of Muslim moral

independence from the West.9 And there is simply no evidence from our tradition that the Prophet Muhammad ever contemplated abolishing slavery.

My

argument is distinct from both of these extremes. I have argued that

Western notions of abolitionist freedom have already fused with Islamic

values, and that it is dangerous to try to extract one from the other.

There are a number of positive benefits from embracing this position.

For one thing, it provides Muslims with a powerful language not only to

challenge slavery, but many other forms of similar domination and

exploitation that go by different names. It seems to me that Muslims who are using this fusion of moral horizons

to critique both Muslim and Western complacency with regards to forms

of oppression analogous to slavery are engaged in an urgently necessary

and positive reinvigoration of the Islamic tradition.

NOTES:

1 Trajectory hermeneutics originated with Christian theologian William Webb. For more on their use, see his 2001 book, Slaves, Women, and Homosexuals: Exploring the Hermeneutics of Cultural Analysis.

2 Jonathan Glassman. “The Bondsman’s New Clothes: The Contradictory Consciousness of Slave Resistance on the Swahili Coast” Journal of African History 32(2): 1991, 277-312.

3 Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī º30; Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim º1661

4 The walāʾ

system then, whatever its faults, was a social compact between master

and slave, and thus often a tool of integration of the latter. See

Ulrike Mitter. “Unconditional Manumission of Slaves in Early Islamic

Law: A Hadith Analysis.” In The Formation of Islamic Law (ed. Wael Hallaq). New York: Routledge, 2008.

5 Unlike

the status of ex-slaves even many postbellum Western societies, the

formerly enslaved in the Islamic world could raise their status

considerably. But that did not erase an existing hierarchy placing the

enslaved at or near the bottom of society.

6 Luke

12:43-48; Qur'ān (Sūra az-Zumar) 39:36. The Apostle Paul’s advice to

the runaway slave Onesimus in the Book of Philemon is filled with

admonishments about a new community of belief between slaves and masters

that does not upend the social hierarchy but nevertheless creates a

sense of moral obligation between the two.

7 For

the Haitian revolutionaries and their creation (not merely co-optation

of) Enlightenment values, see Laurent Dubois, “Enslaved Enlightenment:

Rethinking the Intellectual History of the French Atlantic” Social History 31(1): Feb 2006, 1-14. For the abolitionists, see Adam Hochschild. Bury The Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free An Empire’s Slaves. London: Mariner Books, 2006. For Abdul Kader Kane and the abolition of slavery in Futa Toro, see Rudolph Ware, The Walking Quran, Chapter 3.

8 For Habib Saleh, see Patricia Romero. "'Where Have All the Slaves Gone?' Emancipation and Post - Emancipation in Lamu, Kenya." The Journal of African History 27 (3): 1986, 497-512. For Shaykh Ramiya, see August Nimtz Jr. Islam and Politics in East Africa. The Sufi Order in Tanzania. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1980, 45.

9 Abu Ala Mawdudi was unabashed about this stance. See W.G. Clarence-Smith, Islam and the Abolition of Slavery, 188.

Nathaniel

Mathews is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of

Africana Studies at SUNY-Binghamton. He received a B.A. in History from

Howard University, an M.A. in Global, International and Comparative

History from Georgetown University in 2009, and a Ph.D. in African

History from Northwestern University in 2016, focusing on family

networks and the Swahili-speaking diaspora in the Indian Ocean.

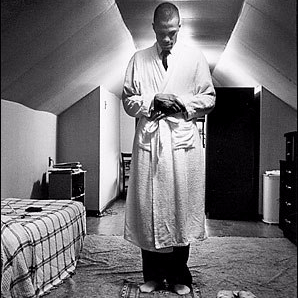

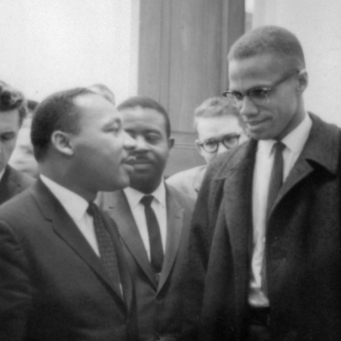

organization

will spend an entire career being a good “moderate Muslim” acquiescing

to the white supremacist notion of collective guilt after the latest

incident puts Muslims in a bad spotlight. This comes at the expense of

having ministries actively addressing the spiritual needs of black folks

in neighborhoods hardest hit by white supremacy and who through internal colonialism

have been ostracized from mainstream America. The strict separation of

religion from the lived material realities of Black people is the trick

of secularism. Both the Negro imam and Muslim immigrant institutions

ultimately get subsumed by a theology that presents no credible threat

to white supremacy.

organization

will spend an entire career being a good “moderate Muslim” acquiescing

to the white supremacist notion of collective guilt after the latest

incident puts Muslims in a bad spotlight. This comes at the expense of

having ministries actively addressing the spiritual needs of black folks

in neighborhoods hardest hit by white supremacy and who through internal colonialism

have been ostracized from mainstream America. The strict separation of

religion from the lived material realities of Black people is the trick

of secularism. Both the Negro imam and Muslim immigrant institutions

ultimately get subsumed by a theology that presents no credible threat

to white supremacy.  Hakeem Muhammad is a Black Muslim Public Intellectual, Public Interest Law Fellow at Northeastern Law School, and Educator at Muslim Empowerment Institute

(MEI). Muhammad’s scholarship is dedicated to Islamic revival in the

black community. He believes that Islam must be restored to having the

transformative effect in once had in mitigating the social ills of

Black America. Muhammad has previously worked in the African-American

Male Initiative working to increase the college retention rates of

Black Male students. He has also taught political philosophy for

Harvard Debate Council and Cal Speech and Debate Camp at U. C Berkeley.

Muhammad is also the author of the forthcoming book, “The Significance of the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan to the Entire Muslim Ummah.”

Hakeem Muhammad is a Black Muslim Public Intellectual, Public Interest Law Fellow at Northeastern Law School, and Educator at Muslim Empowerment Institute

(MEI). Muhammad’s scholarship is dedicated to Islamic revival in the

black community. He believes that Islam must be restored to having the

transformative effect in once had in mitigating the social ills of

Black America. Muhammad has previously worked in the African-American

Male Initiative working to increase the college retention rates of

Black Male students. He has also taught political philosophy for

Harvard Debate Council and Cal Speech and Debate Camp at U. C Berkeley.

Muhammad is also the author of the forthcoming book, “The Significance of the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan to the Entire Muslim Ummah.”